High levels of poverty and inequality have intensified a longstanding sense among Latin Americans that the economic chips are stacked against them. Policymakers should consider voters’ frustration as they seek to boost fiscal sustainability and preserve social stability.

Ilan Goldfajn and Eduardo Levy Yeyati

Project Syndicate

Latin America faces three major macroeconomic problems: subpar growth, fiscal deficits, and rising poverty-driven inequality. Solving them requires addressing all three simultaneously, with a strategy that recognizes the complex interactions with one another.

Latin America was experiencing subpar economic growth well before the COVID-19 crisis, owing to low productivity and investment growth. Average annual per capita GDP growth actually fell by 0.7% in 2015-19, well below the emerging- and developing-economy positive average growth of 2.9%. And the pandemic has weakened the region’s growth prospects even further, with an uneven recovery that, in the absence of structural reforms, could lead to another “lost decade.”

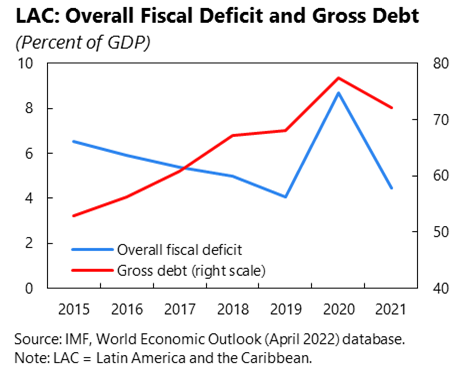

The pandemic has also left Latin America with large fiscal imbalances and debt burdens. From 2019 to 2020, fiscal deficits surged from 4% to 8.7% of GDP (on average), and debt ratios jumped by nine percentage points of GDP. While debt ratios fell in 2021 – reflecting the withdrawal of COVID-related spending and higher inflation – rising interest rates and the associated tightening of global financial conditions mean that the fiscal challenge Latin America faces will intensify.

The interactions between these two policy challenges – growth and fiscal sustainability – are well known. Excessive fiscal deficits can cloud the macroeconomic outlook and cause foreign investment to dry up, leading to lost growth opportunities. At the same time, low growth makes fiscal sustainability harder to achieve. These interlinked problems have weighed heavily on Latin America in the past.

But now these challenges are being amplified further by a third factor: High levels of poverty and inequality – exacerbated by the pandemic’s uneven impact on the population – have intensified a longstanding perception of unfairness. This widespread public sentiment places added social and political constraints on policy reforms.

Already, policymakers are struggling to meet voters’ demands for greater economic well-being, with gains in living standards having stalled in recent years. This partly reflects two weaknesses that have silently plagued the region for decades, and that the pandemic brought to the fore.

First, the state capacity needed to deliver broadly available, high-quality public services is sometimes lacking. This was apparent in the uneven implementation of virus-containment policies, slow health-care and vaccination responses in some areas, and educational losses arising from logistical lapses and discrepancies in access to digital tools during extended school closures.

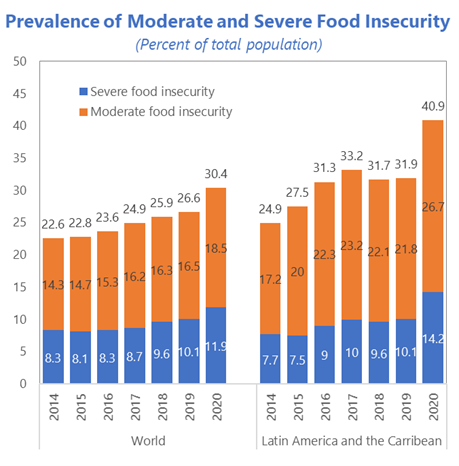

It was also apparent in rising food insecurity. According to the latest report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the share of people suffering from moderate or severe food insecurity in Latin America and the Caribbean increased from 31.9% in 2019 to 40.9% in 2020.

This increase – the biggest experienced by any region in the world – was fueled primarily by the pandemic-driven economic downturn and the lack of adequate support for vulnerable groups during the crisis, though other factors, such as violent conflict and natural disasters, may also have contributed. Now – just when economies were returning to pre-pandemic levels – inflation is threatening to increase food insecurity further.

These failures could leave lasting economic and social scars if not addressed. So will the impact of Latin America’s second hidden weakness: the prevalence of informality in the labor market. During the pandemic, most workers and businesses had to fend for themselves, because, in general, only those with formal incomes could access official income and credit support.

In the aftermath of the latest systemic crisis, efforts to restore fiscal sustainability must be pursued, but with measures that consider their social impact, particularly among those who were excluded from business- and job-protection schemes and endured the pandemic without adequate public support. Latin America is unique in that it comprises developing economies that, for the most part, are also democracies.

This means that, as policymakers attempt to spur growth and rebuild fiscal space, they must recognize and respond to voters’ frustration amid inequality and widespread mistrust of government.

Here, Colombia’s 2021 tax reform holds valuable lessons. The original proposal to reform the value-added and income taxes had to be modified (and include higher corporate taxes) in order to be enacted, after large-scale street protests.

Minimizing the social impact of economic policies is not just a matter of morality. It is also a matter of stability. Policies aimed at ensuring fiscal sustainability can work only if they are also socially and politically sustainable. To that end, they must be complemented by policies that boost structural growth. Policymakers cannot neglect any piece of this puzzle if they aspire to achieve sustainable economic and social gains.

Ilan Goldfajn, a former president of the Central Bank of Brazil, is Director of the International Monetary Fund’s Western Hemisphere Department.

Eduardo Levy Yeyati, a former chief economist of the Central Bank of Argentina, is Dean of the School of Government at Universidad Torcuato Di Tella, Faculty Director of the Center for Evidence-Based Policy, and a non-resident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

Link da publicação: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/latin-america-triple-policy-challenge-by-ilan-goldfajn-and-eduardo-l-yeyati-2022-08

As opiniões aqui expressas são do autor e não refletem necessariamente as do CDPP, tampouco as dos demais associados.