Schwartsman & Associados

I have to confess that I was not particularly optimistic about the prospects of the so called “new fiscal framework”, the new set of rules designed to replace the moribund “spending cap” approved in 2016, but gradually eroded in the past few years. And yet, its announcement proved to be a disappointment even for me.

As I intend to discuss along this note, apart from the appalling scarcity of details surrounding the subject, there are at least two major problems.

The first we pinpoint below is that fiscal policy under this new regime will be more expansionary than under the previous one (ok, under the heroic assumption that it would be respected). Hence, monetary policy would have to be more contractionary than under the previous regime.

The second is that its operation would most likely require much higher revenues, or even this new framework would lead to a politically unfeasible reduction in discretionary spending (therefore investments), unless rules governing the dynamics of mandatory spending would change dramatically, a highly unlikely outcome if you ask me.

Whether Congress is prepared to accept a major increase in taxes remains an open question. Although there are still details to be ironed out, the new framework is based on two main axes. The first one is a path for the primary balance along the next years (more to the point, an interval for the primary balance measured relative to GDP), whereas the second one is a rule limiting the increase in primary spending to a fraction (70% in the base case) of the increase in primary revenues.

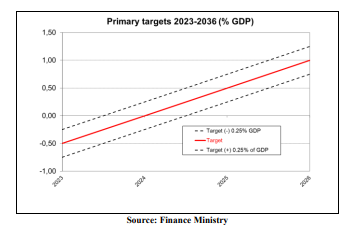

The target path is depicted below. As shown, it departs from a 0.5% of GDP deficit in 2023 (more on that below), which then would become zero in 2024, and finally 0.5% and 1.0% of GDP in respectively 2025 and 2026. Deviations up to 0.25% of GDP would be tolerated.

Just for the record, this path is far more aggressive in terms of deficit reduction than the one originally implied by the now-defunct spending cap. Back then, the primary deficit would be reduced at less than 0.5% of GDP in each year and would require some 4-6 years before turning the primary deficit into a surplus (departing, we add, from a higher deficit than today). In so many words, if it would work as projected, it would be more contractionary than the maligned spending cap at that time.

Having said that, the other axis of the program is a rule determining, at least as a base case, that primary spending growth cannot reach more than 70% of primary revenue growth. More to the point, growth of primary expenditures (the ones currently subject to the spending cap) in, say, 2024 would be limited to 70% of the growth rate of primary revenues observed between June 2022 and June 2023. If it reaches, for instance, 10%, such expenditures could not expand by more than 7% in 2024.

There is, as one can reckon, a problem with such rule: if followed to the letter, it would make spending quite pro-cyclical. Following periods of fast growth, hence strong revenue expansion, spending would increase, whereas in the aftermath of a recession, expenditures would be limited, maybe even reduced, in sharp contrast to the what would be expected under the spending cap (in normal conditions, no change in real spending).

In order to deal with this issue, the basic rule has been amended. Thus, expenditures would rise at least 0.6% in real terms, but also limited to 2.5% in real terms. Hence, should revenues increase less than 0.85% in real terms in a given period, spending will still expand 0.6%; should revenues increase more than 3.57%, expenditure would be capped at 2.5%. This mitigates, but does not eliminate, the procyclicality in spending.

A hypothetical comparison to the current framework, the spending cap, might help. Under current (but quickly evaporating) rules, higher real collection increases the primary balance by the same amount, a development that acts as a brake on the economy, whereas a decline in collection leads to a reduction of the primary balance by the same amount, moderating the decline.

Under the new rules, the increase in collection does not translate in a similar increase in the primary balance, hence being less effective as a brake. On the opposite direction, however, it leads to an even higher deficit, a development that might moderate the decline in activity (it is asymmetrical, as one can see). In both cases, therefore, fiscal policy is more expansionary than under the previous regime.

Implications for monetary policy, nevertheless, will not be well-accepted. Precisely because fiscal policy would be more expansionary regardless of the stage of the business cycle, monetary policy would have to be tighter than under the previous regime. It is not, for instance, that BCB would not be able to cut rates in the downswing; only that it would cut less than it would do under the spending cap.

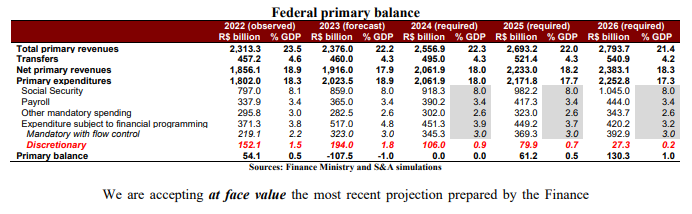

There is, however, another issue, which points to the need to increase substantially primary revenues. This is better illustrated by the table below, which departs from historical data on the federal balance for 2022, as well the latest forecast for 2023.

Ministry on the fiscal performance for 2023, which forecasts a primary deficit at 1.0% of GDP. This conflicts with the 0.5% of GDP target for the year, an issue on which I still await clarification.

From this data we can deduce the maximum increase in spending for 2024 (well, not exactly, since we use year-on-year growth, rather than the 12-month period to June, but hopefully this will not imply a major deviation).

Once we have an estimate for primary spending in 2024 (again, not exactly; I am leaving aside the fact that the rule does not apply to some federal spending), and the target for the federal balance, in the current case, we can find required net revenues, which in this case must be the same as expenditures (duh). Under the assumption that transfers remains a fixed share of total revenues, we can estimate required total revenues as well.

More importantly, however, assuming that mandatory spending evolves in line with recent years (that is, maintaining their share of nominal GDP, which comes from the Finance Ministry forecasts), we can estimate how discretionary spending should evolve in order to be consistent with total primary expenditures.

The same process can be applied to 2025 (when the target for the primary balance is positive, 0.5% of GDP) and 2026 as well.

As one can conclude from the table above, discretionary spending, even under the new rules, would have to be compressed, if total revenues increase just enough to deliver the fiscal target given total expenditure evolution.

Note that I am not using the upper limit for expenditures in this simulation, which would only make the problem worse, that is, further need to reduce discretionary spending.

At the same time, however, the program states that there is a floor for federal investment, which would be inconsistent with simulation results. There are two (not mutually exclusive) conclusions to draw from this result.

The first is that, in order to accommodate discretionary spending (hence investment), primary revenues would have to reach even higher.

The second is that at some point the administration may be tempted to fiddle the rules, as sadly usual in this country, bypassing the constraints imposed by the new fiscal framework, just as the previous administration did with the spending cap.

One way out of the conundrum is to change another assumption made above, namely that mandatory spending would follow the same rules hence keeping its share on GDP.

This is not new. In fact, this is the oldest problem surrounding Brazilian fiscal accounts: there are rules governing the dynamics of mandatory spending that sooner (most likely) or later clash with any limit on total primary expenditures. As long as these rules remain in place, there is simply no reason to believe that the new fiscal framework will fare any better than any of its predecessors.

The alternative, thus, is to increase substantially revenues, presumably by increasing taxation. The tax reform under discussion would not do the job. Not because it is going to be “neutral” (no matter how much I love science fiction and fantasy, I am too old to believe in “neutrality promises”), but because, even if approved now, the new tax regime will not be fully operational for a while, counting the time required to approve complementary legislation, not to mention the far thornier issue of putting it to work.

This leaves the alternative of increasing existing taxes, for instance, income tax.

Such path is far more complex than usually presumed, not only due to possible political hurdles, but mostly because: (a) income tax revenues are shared with states and municipalities; (b) earmarking forces another significant share of proceeds to be spent.

The rule of thumb is that a 1% of GDP in additional income tax increases spending (including transfers) by 0.5% of GDP. It should not be a surprise, thus, the reluctance of previous administrations to rely on additional income tax to fix fiscal problems.

The practice, both in 1999 and in 2002-03 was to push for higher PIS-Cofins, which can be increased in the same year (requires only a 90-day interval) and is fully appropriated by the federal government, at least under current rules. To be sure, it runs in the opposite direction of the tax reform, but, as usual in the country, the urgent comes before the necessary.

It remains to be seen whether Congress will tolerate higher taxes. It has been unenthusiastic, to say the least, about the return of CPMF, as previous administrations can attest, but then there is always the possibility of finding convincing reasons for higher taxes, or maybe even the elimination of some tax breaks (which I would love to see, but still deem unlikely).

Anyway, without higher taxes, this framework will probably not fly.

As opiniões aqui expressas são do autor e não refletem necessariamente as do CDPP, tampouco as dos demais associados.